WHAT IS BIOEQUIVALENCE?

Prof. Dr. F. Cankat Tulunay

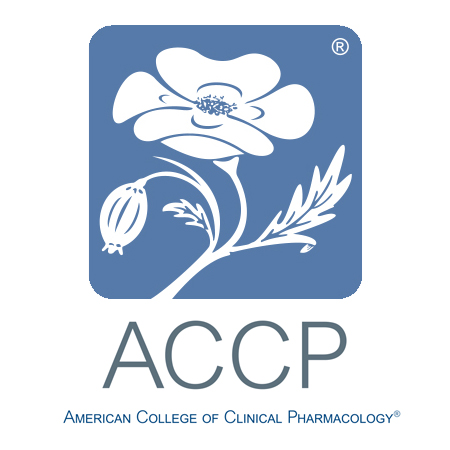

Bioavailability (BA) is the measure of the fraction of an administered drug dose that reaches the systemic circulation and the rate at which it occurs. In other words, it shows how much of a drug reaches the bloodstream and at what speed. Bioavailability is usually calculated from the plasma concentration–time curve. The most important parameters obtained from this curve are: AUC (area under the curve, representing total exposure), Cmax (maximum plasma concentration), and Tmax (time to reach Cmax).

Bioavailability is evaluated in two ways:

- Absolute bioavailability: comparison of the fraction of drug reaching the circulation after oral administration with that after intravenous administration.

- Relative bioavailability: comparison of the same active substance given in different pharmaceutical forms (e.g. tablet vs suspension).

Bioequivalence (BE) refers to the situation where two pharmaceutical products containing the same active ingredient at the same molar dose (for example, an original drug and its generic) show no clinically meaningful differences in bioavailability when administered under similar conditions. In other words, it demonstrates that the rate and extent of absorption are statistically equivalent. For this evaluation, the 90% confidence interval of AUC and Cmax values is generally required to fall within 80–125%.

Bioequivalence studies are the cornerstone of generic drug approval, because they prove that the generic product provides the same efficacy and safety as the original drug.

Bioavailability and bioequivalence studies became systematic in the USA in the 1970s and in Europe in the 1980–1990s. The USA adopted them earlier, while Europe standardized them centrally with the establishment of the EMA.

In Turkey, the concept of “bioavailability” was first introduced by myself in 1976 as “Biological Utility,” and later Prof. Dr. Oguz Kayaalp recommended the Turkish term “Biyoyararlanım,” which has since been accepted as the official translation of bioavailability (Tulunay F.C.: The relationship between plasma drug concentrations and their effects. In: Cardiovascular Diseases and Drug Therapy, Eds. F.C. Tulunay, I.H. Ayhan, S. Kaymakçalan, Agac IS Basim, Ankara, pp.1–24, 1976).

Since then, through the Turkish Pharmacology Society and the Clinical Pharmacology Society, we made significant efforts to ensure that bioequivalence studies became mandatory for generic drugs in Turkey. Initially, we faced strong opposition and even threats from the domestic pharmaceutical industry.

Bioavailability and bioequivalence concepts in Turkey emerged about a decade later than in the rest of the world. In the 1980s, BE was not mandatory in drug registration processes. By the mid-1990s, however, the Ministry of Health began requiring bioequivalence reports for generic drug registrations. At that time, Turkey lacked the infrastructure to conduct these studies domestically.

To fill this gap, Turkey’s first bioequivalence center, **AKFAK (Ankara Clinical Pharmacology Research Center)**, was established by Prof. Dr. F. Cankat Tulunay. AKFAK enabled the conduct of BA/BE studies locally, marking a turning point for both academia and the pharmaceutical sector. This initiative paved the way for Turkey’s generic pharmaceutical industry to comply with international standards. The first bioavailability study in Turkey was carried out by AKFAK (Tulunay FC, Onaran HO, Ergun H, Ucar A, Usanmaz S, Embil K, Tulunay M.: Pharmacokinetics of phenprobamate after oral administration to healthy subjects. Arzneimittelforschung. 1998 Nov;48(11):1068-7). The first bioequivalence study in Turkey was also conducted by us for DEVA company with Ampicillin–Amoxicillin, and DEVA submitted this study to its European registration dossier. Later, following a complaint, the activities of AKFAK were suspended by İEG Director Kemalettin Akalin on the grounds that a private generator was missing (although the building had a central generator). After his retirement, Akalin admitted that the decision was made under pressure and expressed his regret.

The stages of BA/BE development in Turkey can be summarized as follows:

1. Early period (1980s–early 1990s):

- While BE requirements were being implemented globally, drug registrations in Turkey were still based on pharmaceutical quality documents (active ingredient, purity, dissolution).

- BA/BE was not systematically mandatory.

2. 1990s: Initial regulations

- In 1994–1995, the Ministry of Health began requiring BE reports for generic drugs.

- The first studies were performed by AKFAK and inspired other universities.

- However, there were very few domestic centers capable of conducting BA/BE; most companies outsourced to CROs abroad (especially in India and Europe).

3. 2000s: Regulatory consolidation

- In 2001, the “Regulation on the Licensing of Medicinal Products for Human Use” made BA/BE studies legally mandatory in Turkey.

- The Ministry of Health and later the Turkish Medicines and Medical Devices Agency (TITCK) aligned their guidelines with EMA/FDA criteria.

- New BA/BE centers were established (Hacettepe, Ankara, Marmara, Ege Universities, etc.).

4. Post-2010: International harmonization

- TITCK adopted EMA’s 2010 and later guidelines into national practice.

- Turkish BA/BE studies were required to comply with GLP and GCP standards.

- From the mid-2010s, many CROs and university centers began operating. Today, Turkey is a regional hub for BA/BE studies, though some marketed drugs still lack BA/BE evidence.

Developments abroad:

**USA (FDA):**

- 1962 Kefauver–Harris Amendment: required proof of efficacy as well as safety, laying the groundwork for BA studies.

- Early 1970s: FDA required plasma concentration monitoring for drugs with narrow therapeutic index (antiepileptics, digoxin).

- 1977: FDA issued Bioavailability and Bioequivalence Regulations.

- 1984: Hatch–Waxman Act: established BE as the legal foundation for generic drug approval.

**Europe (EMA and pre-EMA national agencies):**

- Mid-1970s: Bioavailability studies began to be required, but implementation differed among countries (Germany, UK, France).

- 1980s: EEC initiated harmonization of drug regulations, including BE for generics.

- 1992: EMA established, providing common criteria for BA/BE.

- 2001/83/EC Directive: made BE mandatory for generic drug licensing.

- Later guidelines (2001, 2010, 2017): refined technical details.

**EMA Bioequivalence Guidelines:**

- 2010 Guideline: standardized BE evaluation (AUC, Cmax, 80–125% rule), included stricter monitoring for NTIDs and modified-release formulations, fasting/fed study requirements.

- 2017 Revision: narrowed AUC limits for NTIDs (90–111%), introduced SABE (scaled average BE) for highly variable drugs (>30% variability), clarified PD/clinical endpoints for non-measurable drugs, and highlighted limitations of classical BE for biologics.

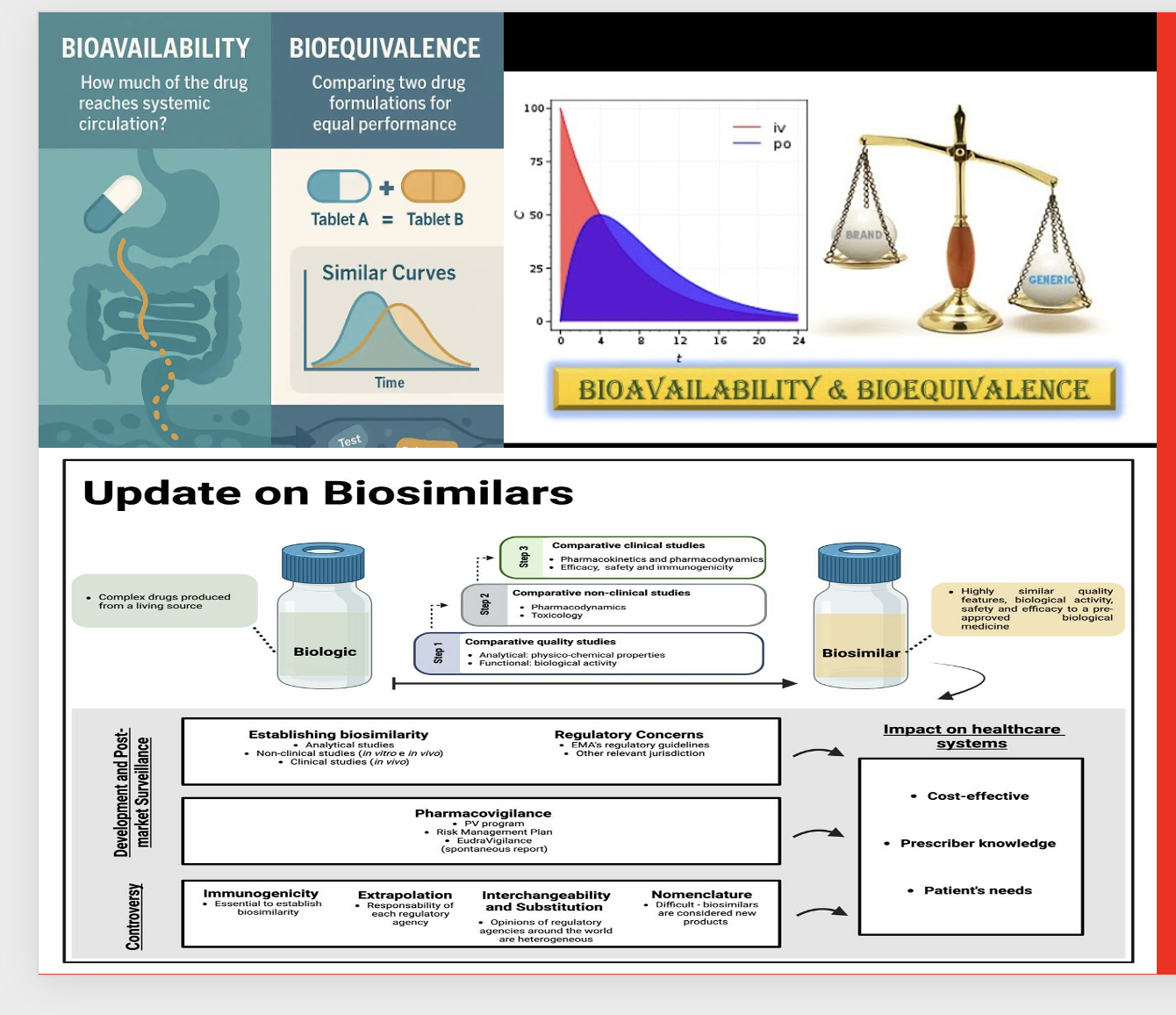

**Biosimilars:**

A biological product can only be considered biosimilar if it demonstrates the same efficacy, safety, and quality as the reference product without clinically meaningful differences. Requirements include:

1. Link to reference product (licensed in EU/US).

2. Molecular characterization (identical amino acid sequence, comparable structure and modifications).

3. Manufacturing (new cell line, GMP compliance, validated process).

4. Stepwise evidence: analytical similarity → nonclinical studies → PK/PD → clinical efficacy/safety equivalence.

5. Indication extrapolation (with scientific justification).

6. Immunogenicity evaluation.

7. Pharmacovigilance and risk management post-marketing.

**Conclusion:**

For a biological product to be approved as a biosimilar, it must demonstrate equivalence in efficacy, safety, and quality at every level—from molecular characterization to clinical outcomes. Neither in vitro tests alone nor a single clinical trial are sufficient; a comprehensive totality-of-evidence approach is mandatory.

**Guide for Clinicians:**

“Biosimilars: A Healio® Guide for Clinicians” (Feldman M., Gibofsky A., Grammel M., Heled Y., Roberts E.T., Cooper J., 2025).