DRUG COSTS: R&D AND VALUE-BASED PRICING

What do the barons of the pharmaceutical industry really think?.. Profit margins of drug companies are higher than those of all other Fortune 500 firms

Prof. Dr. F. Cankat Tulunay

www.klinikfarmakoloji.com

ABSTRACT

The pharmaceutical industry usually justifies high drug prices with narratives about research and development (R&D) costs, financing of innovation and “value-based pricing.” This article critically examines these claims, assessing the gap between production costs and prices, the controversial R&D cost estimates published by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development (CSDD), the real role of public funding, and the industry’s claims about clinical innovation. The evidence shows that companies systematically exaggerate R&D costs; that most genuine scientific breakthroughs originate in research funded by the public sector; that the majority of new drugs are “me-too” products; and that the language of value-based pricing often functions as a political tool to legitimise high prices.

INTRODUCTION

For the past forty years, the pharmaceutical industry has been repeating the same narrative to justify its pricing policies:

“Developing a drug is extremely expensive and risky; therefore high prices are inevitable. Otherwise innovation will stop and patients will be left without medicines.”

This narrative is used—especially in the United States, and increasingly in other countries—to weaken attempts to regulate drug prices and to limit the bargaining power of public authorities (Light & Lexchin, 2012; Avorn, 2015).

This article examines the industry’s claims along three main axes:

(i) the gap between production costs and sales prices;

(ii) the inflation of R&D costs and a critique of the Tufts CSDD estimates;

(iii) the relationship between clinical innovation, value-based pricing rhetoric and reality.

The aim is to offer clinicians and health-policy makers a more realistic, evidence-based framework.

INDUSTRY EXECUTIVES’ RHETORIC AND THE ISSUE OF PROFIT

Fortune 500 data show that the pharmaceutical industry has been one of the most profitable sectors of the US economy for decades. While net profit margins in industries such as the automotive sector are around 3–7%, pharmaceutical margins often lie in the 15–25% range (Public Citizen, 2024). This high level of profitability is clearly reflected in the statements of company executives.

For example, Bayer’s CEO Marijn Dekkers, reacting to India’s decision to grant a compulsory licence for sorafenib (Nexavar), stated:

“We did not develop this medicine for Indians; we developed it for Western patients who can afford it.”

Executives of companies such as Gilead, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, Merck and Roche, when defending the prices of oncology drugs and other high-cost medicines, invoke abstract notions such as “value created,” “funding innovation” and “sustainable R&D” while systematically ignoring production costs and the contribution of public funds.

This rhetorical framework presents the industry as if it were self-sacrificingly working for public health, whereas in practice it serves to protect high prices and profitability. The underlying policy implication can be summarised crudely as: “Those who cannot pay, can die.”

THE GAP BETWEEN PRODUCTION COSTS AND SALES PRICES

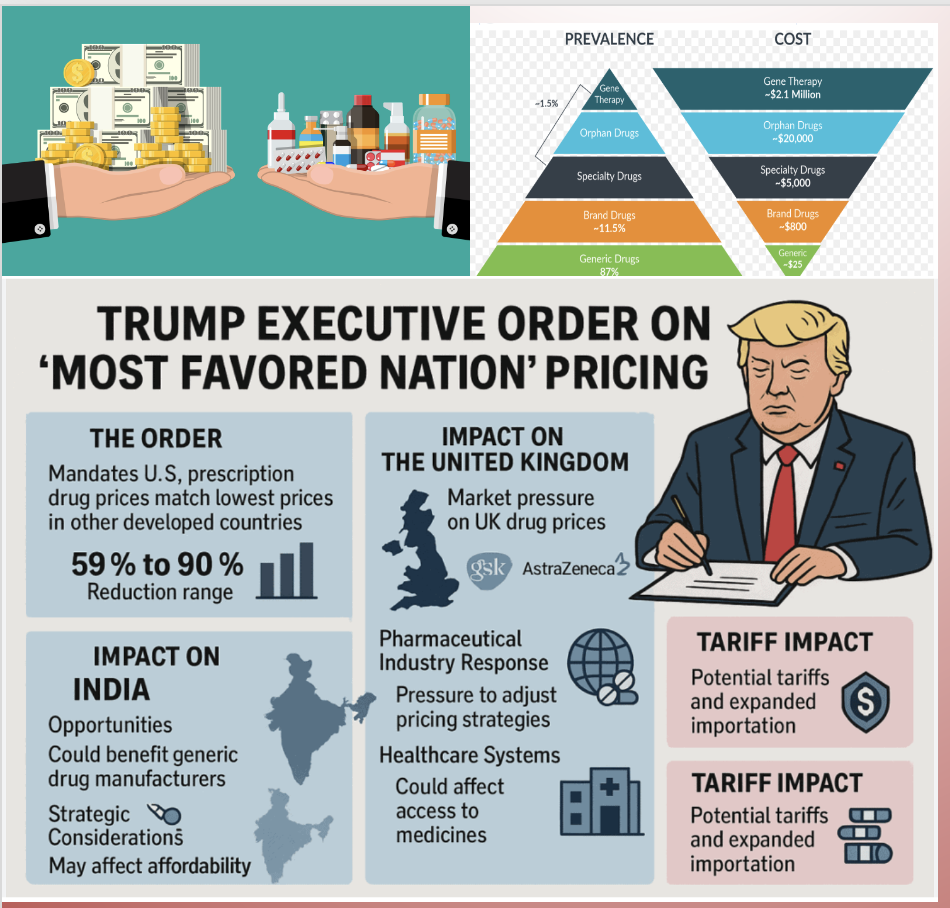

For many modern drugs, there is a striking difference between production costs and list prices. This is particularly evident with gene therapies and biological agents:

- Zolgensma (Novartis): Estimated production cost 100,000–200,000 USD, while the single-dose list price is about 2,125,000 USD.

- Hemgenix: Production cost 200,000–400,000 USD, list price roughly 3,500,000 USD.

- Kymriah (CAR-T): Patient-specific production cost 50,000–100,000 USD; list price about 475,000 USD.

- Sovaldi (Gilead): Production cost around 100 USD, while the US list price for a 12-week course was set at 84,000 USD.

- EpiPen (Mylan): Production cost per kit about 10 USD; list price climbed to as high as 600 USD.

- Ozempic (Novo Nordisk): Monthly production cost in the range of 20–30 USD, yet the US list price is 900–1000 USD per month.

Similarly, analyses by Public Citizen and others show that the total revenue Novo Nordisk generates from its semaglutide-based products (Ozempic/Wegovy) exceeds the company’s annual total R&D spending within a short period. In recent years, the firm’s annual R&D expenditure has been about 4–4.5 billion USD, whereas Ozempic alone had sales of roughly 17 billion USD in 2024; the total revenue of the GLP-1 portfolio exceeds 40 billion USD.

When compared with production costs and reasonable levels of R&D expenditure, this picture demonstrates that drug prices are far removed from any genuine cost-based rationale.

THE R&D COST MYTH AND TUFTS CSDD ESTIMATES

One of the industry’s most frequently used arguments is that “bringing a new drug to market costs about 2.6 billion dollars.” This figure is based on studies published by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development (DiMasi et al., 2003; 2016). DiMasi is effectively a pawn of the pharmaceutical companies, and 55–60% of the Tufts Center’s budget is covered by industry funding. DiMasi and his team use every possible trick to inflate the apparent cost of drug discovery. These studies have serious methodological and transparency problems.

1. Secret data and a selected sample

Tufts’ analyses rely on data from more than 100 compounds provided by around 10 pharmaceutical companies, whose names and details are not disclosed. The raw data are not publicly available, and independent researchers cannot verify the calculations. Moreover, the analysis focuses on products that companies classify as “self-originated” and that are considered the most expensive to develop. Thus, the estimates do not represent a typical average for all drugs.

2. Figures inflated by “opportunity cost”

In Tufts’ 2016 study, the cost of developing a drug is given as 2.6 billion USD. Of this amount, about 1.4 billion USD is direct expenditure, whereas 1.2 billion USD is defined as “opportunity cost.” Opportunity cost—what I might jokingly call the “if my aunt had a beard, she would be my uncle” logic—represents the hypothetical return a company could have obtained if it had invested its R&D spending in a stock index fund instead. Presenting such speculative gains as part of actual R&D costs and selling them to the public as “the cost of drug development” is scientifically and ethically highly problematic.

A British Medical Journal analysis deconstructed an earlier Tufts estimate of 1.3 billion USD and showed that half of this figure was opportunity cost, and that half of the remaining 650 million USD was offset by tax credits. Thus the actual cash outlay falls to around 330 million USD. Furthermore, this amount applies only to the most costly 20% of drugs; when adjusted to all new drugs, the average cost per drug is approximately 90 million USD (Light & Lexchin, 2012).

3. Ignoring public funding

The Tufts calculations systematically exclude the role of public funding. Yet the literature shows that a substantial proportion of the most “transformative” drugs developed in recent decades have emerged from basic science funded by the public sector (Avorn, 2015). Disease mechanisms, molecular targets and initial candidate molecules are often developed in university laboratories supported by NIH and similar agencies. The private sector frequently enters the picture later, licensing these findings and taking over commercialisation.

Gilead’s hepatitis C drug sofosbuvir (Sovaldi) is a classic example: the molecule was discovered by an academic researcher, developed through publicly funded research, and then purchased by Gilead, which went on to earn billions of dollars in a short time.

4. The Public Citizen assessment (Public Citizen is the largest consumer-rights protection organisation in the world.)

Public Citizen’s report examined in detail the R&D cost narrative propagated by drug companies and their lobbying organisations and reached the following conclusions:

- The per-drug cost figures claimed by the industry are exaggerated and misleading.

- DiMasi’s own data indicate that the real cost is approximately 110 million USD in 2000-dollar terms.

- Company data show that mean R&D costs in the 1990s were in the range of 57–71 million USD.

- A substantial portion (about 50–60%) of the discovery and development costs of best-selling drugs is actually borne by public funds.

- The industry has spent hundreds of millions of dollars on lobbying to block access to R&D records.

- Since the 1980s, the pharmaceutical sector has been one of the most profitable industries in the United States, with net profits several times higher than in many other sectors.

THE MYTH OF CLINICAL INNOVATION AND “ME-TOO” DRUGS

Another argument frequently used to justify high prices is the rhetoric of an “innovation crisis.” Industry representatives claim that discovering new drugs has become extremely difficult, and that rising prices are therefore inevitable. However, historical data do not support this claim.

Analyses of FDA data show that, although the approval rate for new molecular entities (NMEs) has fluctuated since the 1950s, the long-term average has remained relatively stable, without evidence of a true “collapse” (Munos, 2009). The real problem is not the number of new drugs but the fact that most of them do not offer meaningful clinical advantages compared with existing therapies.

Of the 218 drugs approved by the FDA between 1978 and 1989, only 15.6% were classified as important therapeutic innovations; the vast majority consisted of minor variations that could be labelled as “me-too” products. Similarly, the Barral report covering 1974–1994 found that only 11% of newly marketed drugs were genuinely innovative in pharmacological and therapeutic terms. Independent evaluations show that since the 1990s, 85–90% of new drugs have provided either very limited or no additional clinical benefit compared with existing options.

In light of these findings, Light and Lexchin (2012) argue that the so-called innovation crisis is a myth and that the real crisis is a lack of clinically meaningful innovation. Nevertheless, companies market me-too molecules with minimal differences as if they were “breakthrough therapies,” use a variety of tools to shape prescribing behaviour, and legitimise their high prices through the rhetoric of “value.”

THE RHETORIC OF VALUE-BASED PRICING

In recent years, pharmaceutical companies have frequently invoked the concept of “value-based pricing” (VBP). The central claim is that a drug’s price should not be based on production costs but on the “value” it provides to patients and society. Value is typically defined using indicators such as overall survival (OS), quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), reductions in morbidity and savings in health-system costs (Drummond et al., 2015).

In theory, value-based pricing could help health systems use resources more efficiently, prevent excessive spending on low-value drugs and enable payers to negotiate prices based on scientific evidence. Risk-sharing agreements (outcomes-based agreements) might allow dynamic price adjustments according to real-world outcomes.

However, in practice VBP has serious problems and limitations:

- The concept of value is ethically and methodologically contested. Measures such as QALYs may lead to discriminatory outcomes for elderly and disabled people (Williams, 1997; Ubel & Loewenstein, 2008).

- Clinical data are often limited. Many new drugs are approved on the basis of small, short-term trials that rely on surrogate endpoints, making early value estimates unreliable.

- VBP can be used to justify high prices. In oncology and rare diseases, companies can demand annual prices of 100,000–300,000 USD for therapies that offer only a few months of survival benefit, and defend these prices as reflecting “high value” (Light & Lexchin, 2012).

- Implementation in low- and middle-income countries is difficult. Many such countries lack the data infrastructure, HTA capacity and long-term follow-up systems required for genuine VBP.

- Industry-sponsored data can be biased. Results can be manipulated through subgroup analyses, selected endpoints and publication bias, undermining the reliability of value calculations.

Therefore, value-based pricing on its own is not a solution and often becomes a tool for rationalising high prices. For it to be effective, robust independent HTA institutions, transparent data sharing, recognition of the role of public funding and constraints on market power are essential (OECD, 2019).

CONCLUSION

The available evidence indicates that the pharmaceutical industry’s narratives about R&D costs, innovation and value are not convincing. The huge gap between production costs and sales prices, the methodological weaknesses of Tufts CSDD estimates, the systematic neglect of the decisive role of public funding, and the fact that most new drugs provide only limited clinical benefits all undermine these narratives. In recent years, companies have increasingly focused on developing high-priced biotechnological products that can be sold at exorbitant prices, while largely ignoring the medicines that the majority of patients actually need—analgesics, antihypertensives, antibiotics, tuberculosis drugs and so on.

For a realistic, fair and sustainable medicines policy, the following steps are essential:

- full transparency regarding R&D costs and public contributions;

- restricting reimbursement for me-too drugs;

- placing marketing and lobbying expenditures under regulatory scrutiny;

- implementing value-based pricing within an independent and ethically robust framework;

- and ensuring that pricing of products originating from publicly funded research reflects the public interest.

Otherwise, the R&D myth and the rhetoric of “value” will continue to function merely as tools for protecting high profits and corporate interests.

In Turkey, drug prices are determined by perhaps one of the strangest systems in the world. It is probably unique to Turkey that, in some cases, the original brand drug is cheaper than its generic. For many medicines, there is little or no price difference between originator and generic products. The Turkish Medicines and Medical Devices Agency (TİTCK) should transparently disclose to the public how drug prices are set in Turkey.

In Turkey, TİTCK should not grant marketing authorisation to every product that comes along, should not treat drugs with no true equivalent worldwide as if they were equivalents, and the Social Security Institution (SGK) should base its reimbursement policy on scientific methods. A truly rational medicines policy must rely on serious pharmacoeconomic evaluations.

If these steps are not taken, the R&D myth and the rhetoric of “value” will continue to exist solely as instruments to protect high profits and corporate interests.

REFERENCES

Avorn J. The $2.6 Billion Pill—Methodologic and Policy Implications. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1877-1879.

DiMasi JA, Hansen RW, Grabowski HG. The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs. J Health Econ. 2003;22(2):151-185.

DiMasi JA, Grabowski HG, Hansen RW. Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs. J Health Econ. 2016;47:20-33.

Drummond M, Sculpher M, Claxton K, Stoddart G, Torrance G. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. Oxford University Press; 2015.

Light DW, Lexchin J. Pharmaceutical R&D: what do we get for all that money? BMJ. 2012;345:e4348.

Munos B. Lessons from 60 years of pharmaceutical innovation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:959–968.

OECD. Value-Based Pricing in Health Care. OECD Health Working Papers; 2019.

Public Citizen. Pharmaceutical Research Costs: The Myth of the $2.6 Billion Pill. Public Citizen; 2024.

Ubel PA, Loewenstein G. Disabling the QALY: Why QALYs are flawed. Health Econ. 2008;17:423–432.

Williams A. QALYs and ethics: A health economist’s perspective. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(2):215–226.

This article was prepared with the support of AI tools