Corruption, Industry Influence, and the Crisis of Scientific Impartiality at the FDA

Prof. Dr. F. Cankat Tulunay – www.klinikfarmakoloji.com

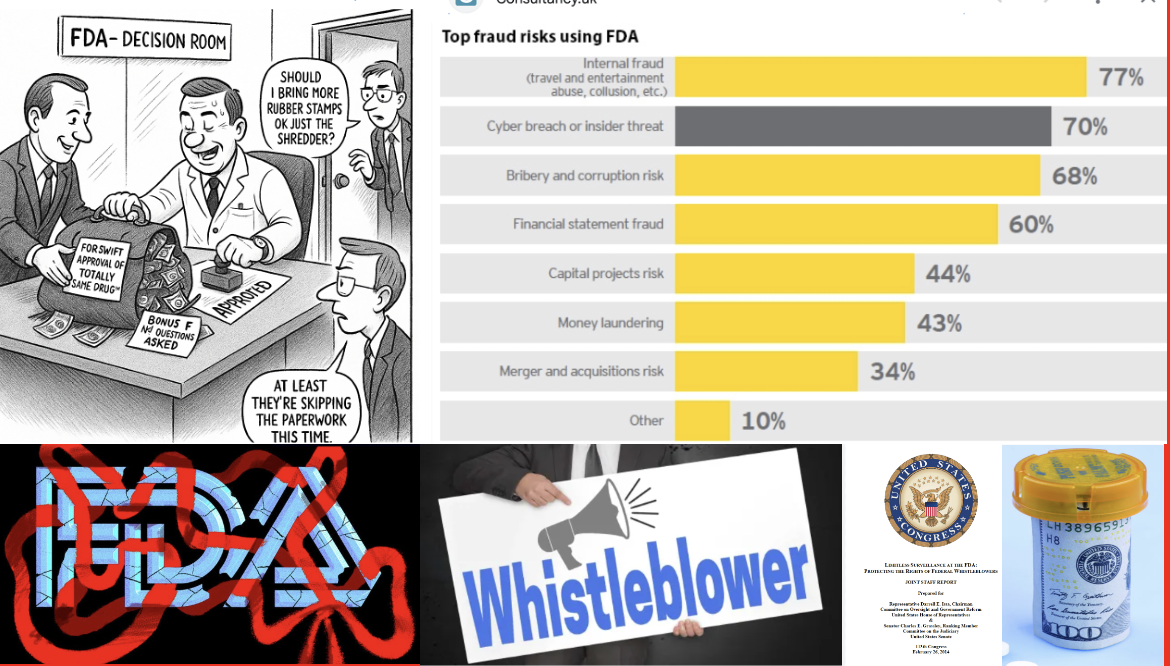

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is regarded as the world’s most influential regulatory authority in drug safety, efficacy, and public health protection. However, throughout its history, recurring cases of corruption, conflicts of interest, industry pressure, and financial dependency have raised serious concerns about the sustainability of its regulatory independence. This paper examines ethical vulnerabilities ranging from direct bribery to structural financial dependence, including lobbying activities, advisory board conflicts, industry-funded research, and mechanisms of data suppression. Findings indicate that while illegal bribery is rare, legally sanctioned financial ties can systematically influence FDA decisions.

The Scope of Industry Influence on the FDA

In the United States, the pharmaceutical and health product industry is the top spender in federal lobbying. Between 1999 and 2018, total lobbying expenditures reached $4.7 billion, averaging $233 million per year. In 2022, spending peaked at $373.7 million — the highest in history. The main actors include PhRMA, Pfizer, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, and BIO. For example, PhRMA spent $422 million and Pfizer $219 million during that period. The industry also contributed $414 million to political campaigns between 1999 and 2018, targeting key lawmakers serving on health-related committees. By 2025, 1,682 registered lobbyists were working for the pharmaceutical industry (OpenSecrets, 2025).

These data demonstrate a systematic strategy by which the pharmaceutical industry influences U.S. health policy through both direct lobbying and indirect campaign financing. Lobbying has become an institutionalized mechanism of influence.

Legal Framework and the Problem of Bribery

Direct bribery is prohibited under U.S. federal law and carries severe criminal penalties. The FDA’s Office of Ethics and Integrity requires employees to disclose financial interests and complete ethics training.

Nonetheless, historical cases of corruption exist. The 1989 Generic Drug Scandal marked a turning point: several FDA officials accepted cash and gifts from generic manufacturers in exchange for expedited approvals based on falsified bioequivalence data. Companies such as Bolar Pharmaceutical and Barr Laboratories were implicated; four FDA officials were convicted, and numerous approvals were revoked (GAO, 1990; Harris, New York Times, 1989).

PDUFA and Financial Dependency

The Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) of 1992 fundamentally altered the FDA’s funding structure. Under this law, application and annual fees paid by pharmaceutical companies became a major source of the agency’s budget. By 2022, user fees accounted for about 46% of the FDA’s total budget and 66% of its human drug program. While PDUFA accelerated drug approvals and fostered innovation, it also rendered the FDA financially dependent on the industry it regulates. Negotiating performance goals directly with companies undermines the perception — and often the reality — of regulatory independence (Carpenter, NEJM, 2010).

Lobbying and Political Advocacy

From 1999 to 2022, the pharmaceutical industry spent over $5 billion on lobbying. These funds influenced major legislative outcomes — for instance, the Medicare Modernization Act (2003), which prohibited Medicare from negotiating drug prices. Although the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA, 2022) partially reversed this restriction, the industry fiercely opposed it. Academic research shows that lobbying significantly increases both the likelihood of drug approval and post-approval market capitalization (Dranove & Meltzer, J Health Econ, 2018). This reflects a textbook case of regulatory capture — when a regulator is effectively controlled by the industry it oversees.

Bribery Cases by Pharmaceutical Companies and Countries

- Alexion Pharmaceuticals (now AstraZeneca plc) – Between 2010 and 2015, Alexion made improper payments to public officials in Turkey, Russia, Brazil, and Colombia. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) found that Alexion Turkey transferred about $1.3 million through third-party consultants, some of which was directed to government officials as cash, gifts, and meals. Alexion settled the charges for $21 million. Although U.S. authorities confirmed misconduct, Turkish courts did not establish domestic criminal liability.

- Pfizer – Paid $60 million to settle charges for bribery of officials in Bulgaria, China, Croatia, Czech Republic, Italy, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Serbia.

- Eli Lilly – Paid $29.4 million for bribery in Russia, Brazil, China, and Poland.

- Johnson & Johnson – Paid $70 million for bribery in Greece, Poland, Romania, and Iraq.

- AstraZeneca – Paid $5.5 million for bribery in China and Russia.

- Teva Pharmaceuticals – Paid $519 million for bribery in Russia, Ukraine, and Mexico.

- Sanofi – Paid $25 million for bribery in Kazakhstan, Lebanon, and the United Arab Emirates.

- Novartis / Alcon – Paid $345–346 million for bribery in Greece, Vietnam, and South Korea.

- GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) – Fined 3 billion yuan (~$489 million) for widespread bribery in China.

In Turkey, Novartis was accused in 2016 of paying approximately $85 million in bribes to secure government contracts and physician influence, though both the Turkish Ministry of Health and Novartis officially denied the allegations.

Revolving Door Dynamics and Advisory Committees

Many senior FDA officials transition to executive, advisory, or board positions in the pharmaceutical industry shortly after leaving public service — a phenomenon known as the revolving door. Although limited post-employment restrictions exist (such as one-year contact bans), indirect lobbying often bypasses them. This circulation fosters systemic bias and undermines regulatory credibility.

FDA advisory committees are meant to provide independent scientific expertise, yet members’ financial ties to companies frequently raise conflict-of-interest concerns. Studies show that members with financial relationships are significantly more likely to vote in favor of drug approval (Lo & Field, JAMA, 2009; Lenzer, BMJ, 2016).

A striking case is rosiglitazone (Avandia) — approved despite severe cardiovascular risks. Subsequent investigations revealed that several panelists had consulting contracts with GlaxoSmithKline (Ridker, JAMA, 2007).

Industry-Funded Clinical Trials and Scientific Bias

Roughly 70% of all clinical trials are industry-funded, and such studies are 2–3 times more likely to report positive results compared to independent ones (Lundh et al., BMJ, 2017). Industry sponsorship influences design, comparator choice, and reporting. Financial relationships among industry, scientific investigators, and academic institutions are widespread. Conflicts of interest arising from these ties can influence biomedical research in important ways (Bekelman et al., JAMA, 2003).

For example, the independent ALLHAT trial (JAMA, 2002) — funded by the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute — found that inexpensive diuretics were as effective as newer, costly antihypertensives. In contrast, the VALUE trial (Pfizer-sponsored) concluded that valsartan was as effective as amlodipine, though closer analysis showed delayed blood pressure control and higher cardiovascular event rates (Julius et al., Lancet, 2004). Such discrepancies illustrate how funding sources can shape both methodology and outcomes.

Comparator and Dose Bias in Study Design

Pharmaceutical companies often manipulate comparator choice or dosing to make their products appear more effective or safer — a subtle but pervasive form of scientific misconduct.

- Paroxetine (Paxil, GSK) – “Study 329” claimed efficacy in adolescent depression but involved selective reporting and concealed suicidal risk (Le Noury et al., BMJ, 2015).

- Rofecoxib (Vioxx, Merck) – The VIGOR and APPROVe trials compared rofecoxib to naproxen, ignoring naproxen’s cardioprotective effects. High (50 mg/day) non-marketed doses were used to favor outcomes (Topol, NEJM, 2004).

- Gabapentin (Neurontin, Pfizer) – Subtherapeutic comparators and “p-hacking” were used to inflate efficacy (Steinman et al., NEJM, 2006).

- Statin trials – New statins were often compared against weak or low-dose agents, creating artificial “superiority” (Abramson & Wright, BMJ, 2007).

- Oseltamivir (Tamiflu, Roche) – Selective publication of favorable studies exaggerated antiviral benefit; Cochrane review later found minimal effect (Jefferson et al., Cochrane Review, 2014).

These practices distort evidence, hasten FDA approvals, and create an illusion of superior efficacy and safety.

Suppression of Negative Data (Publication Bias)

“Publication bias,” “selective outcome reporting,” and “data suppression” refer to the intentional withholding or manipulation of negative findings. Such suppression conceals inefficacy or toxicity, boosting approval odds and commercial success. Mechanisms include selective reporting, omission of entire negative studies, and data “spinning” through subgroup analyses.

Examples:

- SSRI Antidepressants – Turner et al. (NEJM, 2008) found that 31% of FDA-submitted SSRI trials were negative, yet only 3% appeared negative in published literature. The overall efficacy of SSRIs was thus overstated by 94%.

- Paroxetine (Study 329) – GSK concealed suicidal ideation data, later fined $3 billion by the U.S. Department of Justice.

- Gabapentin (Pfizer) – Of 21 off-label trials, only 2 positive ones were published; the rest were buried (Steinman et al., NEJM, 2006).

- Tamiflu (Roche) – Eight negative trials were withheld for a decade; full data later showed minimal benefit (Jefferson et al., BMJ, 2014).

- Vioxx (Merck) – Mortality data were omitted from NEJM articles, contributing to an estimated 88,000 heart attacks before withdrawal (Curfman et al., NEJM, 2005).

Such suppression skews meta-analyses and clinical guidelines. Although trial registration on ClinicalTrials.gov became mandatory in 2007, as of 2022, 40% of trials remained unreported (DeVito et al., Lancet, 2022).

Ethical and Institutional Reform

Suppression of unfavorable data and design manipulation may not always constitute overt fraud, yet they endanger public health to a similar degree.

In the United States, such practices are often prosecuted under the False Claims Act, the Consumer Protection Law, and whistleblower (qui tam) suits.

In Europe, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) introduced the Data Transparency Policy in 2014, mandating public access to clinical data.

Future FDA reforms must focus not only on data accuracy but also on data visibility — ensuring that all evidence, favorable or not, remains publicly accessible. Scientific transparency is the cornerstone of public trust and patient safety.

Broader Context and the Case of Turkey

Although this analysis focuses on the FDA, similar challenges exist worldwide — including in Turkey.

The establishment of Turkey’s Pharmaceutical Licensing Commission (Ruhsat Komisyonu) under the Bülent Ecevit Government marked a turning point.

Based on Law No. 1262 on Pharmaceuticals and Medicinal Preparations, the Regulation on Licensing introduced a provision that commission members would henceforth be appointed by the Council of Ministers, not directly by the Ministry of Health.

This reform was officially published in the Official Gazette on April 11, 1978 (Issue No. 16282).

Prior to this, licensing evaluations were conducted by technical boards within the General Directorate of Pharmaceuticals and Pharmacy (İEGM), whose members were directly selected — and occasionally replaced — by ministry officials, allowing significant influence from industry and bureaucratic interests.

The 1978 reform introduced, for the first time, a semi-autonomous commission composed of scientists, clinicians, and pharmacologists officially appointed by the Council of Ministers. As one of its founding members, I can attest that the commission represented a historic reform in Turkey’s pharmaceutical governance:

- Dozens of unnecessary or unsafe drugs had their licenses revoked.

- Preparations containing barbiturates or tincture of opium, particularly cough syrups, were withdrawn.

- Improper dosages and irrational fixed-dose combinations were removed from the market.

However, after the 1980 military coup, the decree establishing this independent structure was repealed, reverting authority to ministry-controlled appointments.

Since then, regulatory independence has eroded, and decision-making once again favors industrial interests over public health.

Without a fully independent national drug authority, it remains impossible to ensure transparency, accountability, and evidence-based regulation in Turkey’s pharmaceutical system.

Conclusion

While direct bribery within the FDA is rare, the agency’s structural financial dependency, lobbying pressure, advisory conflicts of interest, and industry-funded research mechanisms exert profound indirect influence on decision-making.

These forces distort the delicate balance between innovation and safety, erode public confidence, and compromise the integrity of science.

Sustainable solutions require:

- continuous oversight,

- complete transparency,

- empowerment of independent public research, and

- restoration of the FDA’s institutional autonomy grounded in the public interest.

The same principles apply globally — including Turkey — where the creation of a truly independent drug regulatory body is essential for restoring credibility and protecting citizens’ health.

References

Lundh A et al. BMJ 2017;356:i6770.

Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; MR000033.

ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. JAMA 2002;288:2981–2997.

Julius S et al. Lancet 2004;363:2022–2031.

Le Noury J et al. BMJ 2015;351:h4320.

Topol EJ. NEJM 2004;351:1707–1709.

Steinman MA et al. NEJM 2006;354:1579–1586.

Jefferson T et al. Cochrane Rev 2014; CD008965.

Turner EH et al. NEJM 2008;358:252–260.

Curfman GD et al. NEJM 2005;353:2813–2815.

Bekelman JE et al. JAMA 2003;289:454–465.

DeVito NJ et al. Lancet 2022;400:103–112.

Lenzer J. BMJ 2016;353:i2139.

Lo B, Field MJ. JAMA 2009;301:1365–1368.

Carpenter D. NEJM 2010;362:1162–1165.

Dranove D, Meltzer D. J Health Econ 2018;60:1–12.

Note: For further details, see “Can Drug Companies Bribe the FDA? Unveiling the Truth Behind Pharmaceutical Influence”, DrugPatentWatch (https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/can-drug-companies-bribe-the-fda/).

AI support obtained in this article